SEOUL — When Hwang Sok-yong, now 83, began writing his new novel Halmae, he did something that might have seemed unthinkable just a few years ago: he asked an artificial intelligence to help him think.

The news, when it surfaced, landed like a provocation in literary circles. Here was one of Asia's most distinguished writers—a man who has spent six decades wrestling with questions of history, exile and the human condition—turning to ChatGPT for narrative structure. In a culture that often equates technological fluency with youth, the image felt quietly radical.

Yet Mr. Hwang, speaking in a recent video interview, treats the collaboration as something far more ordinary. "It's a much better time to write," he said simply. The machine, he explained, is not a ghostwriter. It is a thinking partner.

The Conversation, Not the Automation

Mr. Hwang was careful with his language. The A.I. did not write the novel. It argued with him.

He arrived at the machine with what he calls the "basic content"—a 600-year-old zelkova tree, a historical time span, a sense of form—and asked it to respond. The system offered five possible narrative structures. Several stylistic options. Mr. Hwang questioned its choices. It defended them. They debated again.

"If you don't bring anything to the conversation," he said, "there's nothing to talk about."

What followed was not automation but preparation. He created files labeled "structure," "form," "philosophical background." He fed the machine references to Heidegger's concept of time, Buddhist notions of impermanence, ecological memory. The A.I. helped gather and organize. But the writing itself—sentence by sentence—remained stubbornly human.

The machine prepared the ground. The author built the house.

The Danger of Outsourcing Thought

For Mr. Hwang, artificial intelligence amplifies what already exists. Without intellectual groundwork, the conversation collapses into noise.

This is where many misunderstand A.I.'s promise, he argues. The danger is not that machines will replace writers. The danger is that writers will stop preparing.

A generation of novelists has grown up believing that craft can be outsourced, that depth can be purchased, that a prompt can substitute for years of reading and thinking and living. Mr. Hwang's use of A.I. suggests the opposite: that the machine is only as intelligent as the mind directing it.

"Garbage in, garbage out," he said. "But also: genius in, amplified genius out."

The Problem of Smoothness

Yet Mr. Hwang harbors no romantic illusions about technology's limits. Artificial intelligence, he observes, tends toward the smooth. Too clean. Too resolved.

He compares it to the shift from vinyl to digital sound: technically precise, emotionally thinner. Literature, by contrast, depends on roughness—on gaps, hesitations, and silences where the reader must intervene and complete the meaning.

Genre fiction may be different. Crime novels, with their puzzles and procedural logic, seem well suited to algorithmic imagination. Serious literature is not. It requires ambiguity, unfinished meanings, and the kind of narrative "negative space" that machines still struggle to leave intact.

"The blank page is where the reader enters," he said. "Machines tend to fill it."

A Novel Without Humans

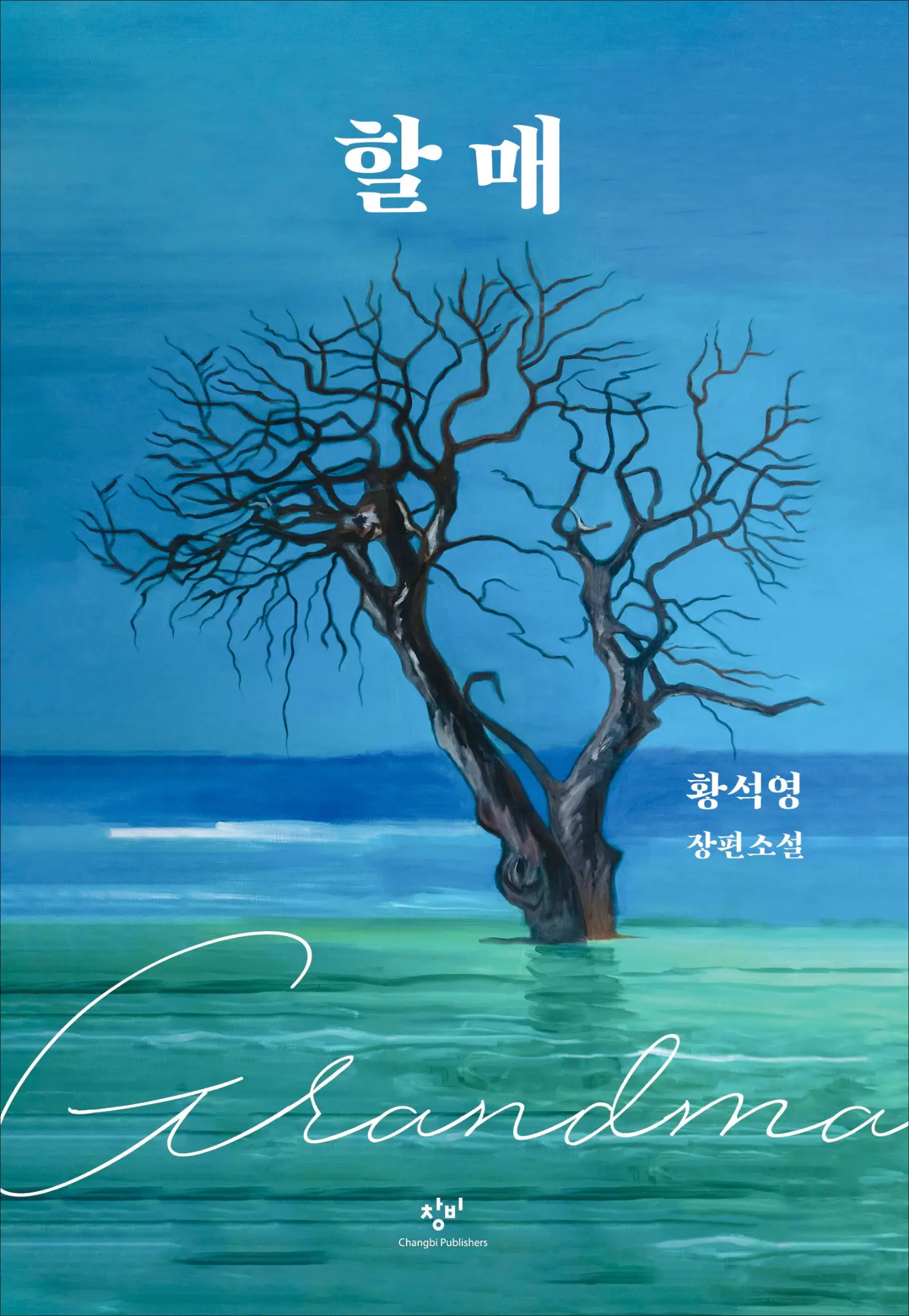

Halmae, published this month by Changbi Publishers, makes this argument formally. For nearly half its length, no humans appear. The narrative belongs to birds, mudflats, insects, and above all, a tree whose rings hold centuries of memory.

Human history—war, famine, colonialism—passes through this nonhuman time rather than organizing it. Humans appear, but they are not the center. They are visitors in a story that belongs to the tree.

The choice is philosophical as much as aesthetic. "Even if humans disappear," Mr. Hwang said, "meaning doesn't." Meaning does not belong exclusively to us. The novel's ecological scale resists human-centered storytelling, reminding readers that history is not always told by those who speak the loudest.

Technology as Continuity, Not Rupture

Mr. Hwang's comfort with artificial intelligence becomes less surprising when viewed against his entire creative life. He wrote early novels by hand. Then with electric typewriters. Then word processors. He serialized fiction online before it was fashionable. He urged poets to experiment with Twitter when others dismissed it.

He has always been in dialogue with his own time, adopting tools not because they were new, but because they allowed him to think differently.

Artificial intelligence, in this lineage, is not a rupture. It is a continuation.

What matters is not the novelty of the tool, but whether the artist remains in genuine dialogue with it—whether they bring something to the conversation, or simply wait for the machine to tell them what to think.

The Last Line Comes Home

The novel ends with the tree speaking directly to the reader: "Where have you been? You're only coming back now?"

It is a line addressed outward, but also inward, to the author himself. After decades of exile, travel, and upheaval, Mr. Hwang has chosen a place to return to, to live, and eventually to die.

In that sense, Halmae is not a book about artificial intelligence at all. It is a reminder that tools change, but the work remains the same: to pay attention, to prepare deeply, and to leave enough space for meaning to arrive on its own terms.

The machine can help you think. But it cannot think for you. Not yet. Perhaps not ever.

Watch the Full Interview

Video: "83세 작가와 AI의 만남" (An 83-Year-Old Writer Meets AI) from 이혜성의 1% 북클럽 (Hye-sung Lee's 1% Book Club)