A Bowl That Remembers the City: Inside Cheongjinok's Haejangguk

SEOUL — There are cities that speak loudly, and there are cities that whisper. Seoul does both. But if you wish to hear its whisper—the low, enduring voice that has survived speed, fashion, and forgetting—you do not look up at towers. You lower your head over a bowl.

That bowl, in central Seoul, is haejangguk (해장국), the soup that has sustained this city through hangovers, exhaustion, and the quiet desperation of dawn. And the place where it lives, unchanged for decades, is Cheongjinok (청진옥).

The Invisible Border

A foreign traveler usually arrives with a map, a phone glowing with directions, a schedule heavy with must-sees. But Cheongjinok does not announce itself. It does not perform. It waits.

From Gwanghwamun Station or Jonggak Station, one walks into narrower streets. The city contracts. Glass gives way to concrete. Noise thins into the sound of footsteps and bowls. The sign is modest. The entrance is narrow. There is no invitation in English.

This absence is deliberate, though not strategic. Cheongjinok does not explain itself.

To arrive here is to cross an invisible border—from tourist Seoul to working Seoul. This distinction is everything.

A Space Without Performance

Inside, the room is bright but undecorated. Tables are close. Movement is efficient. The staff speaks little, not from rudeness but from habit. This is a place designed for eating, not lingering.

For a foreign visitor accustomed to hospitality rituals—greetings, smiles, small talk—this can feel abrupt. Yet soon it becomes clear: nothing here is unnecessary. The menu is short. The choice is simple. Seonji haejangguk (선지해장국) arrives without ceremony.

Taste as Memory, Not Flavor

The soup is not dramatic. There is no sharp spice, no sweet finish, no theatrical heat. Instead, there is balance.

The broth is clear but deep, carrying the quiet labor of long boiling. Inside are seonji (선지, coagulated ox blood), woogeoji (우거지, dried napa cabbage), and beef offal. These ingredients may challenge foreign sensibilities, but the taste itself does not challenge—it persuades.

This is not food that demands admiration. It asks for trust.

A foreign visitor realizes, mid-spoon, that this is not a dish designed to impress newcomers. It was made for people who had no time to be impressed: workers at dawn, journalists before deadlines, clerks before opening hours. Taste here is not an event. It is a condition.

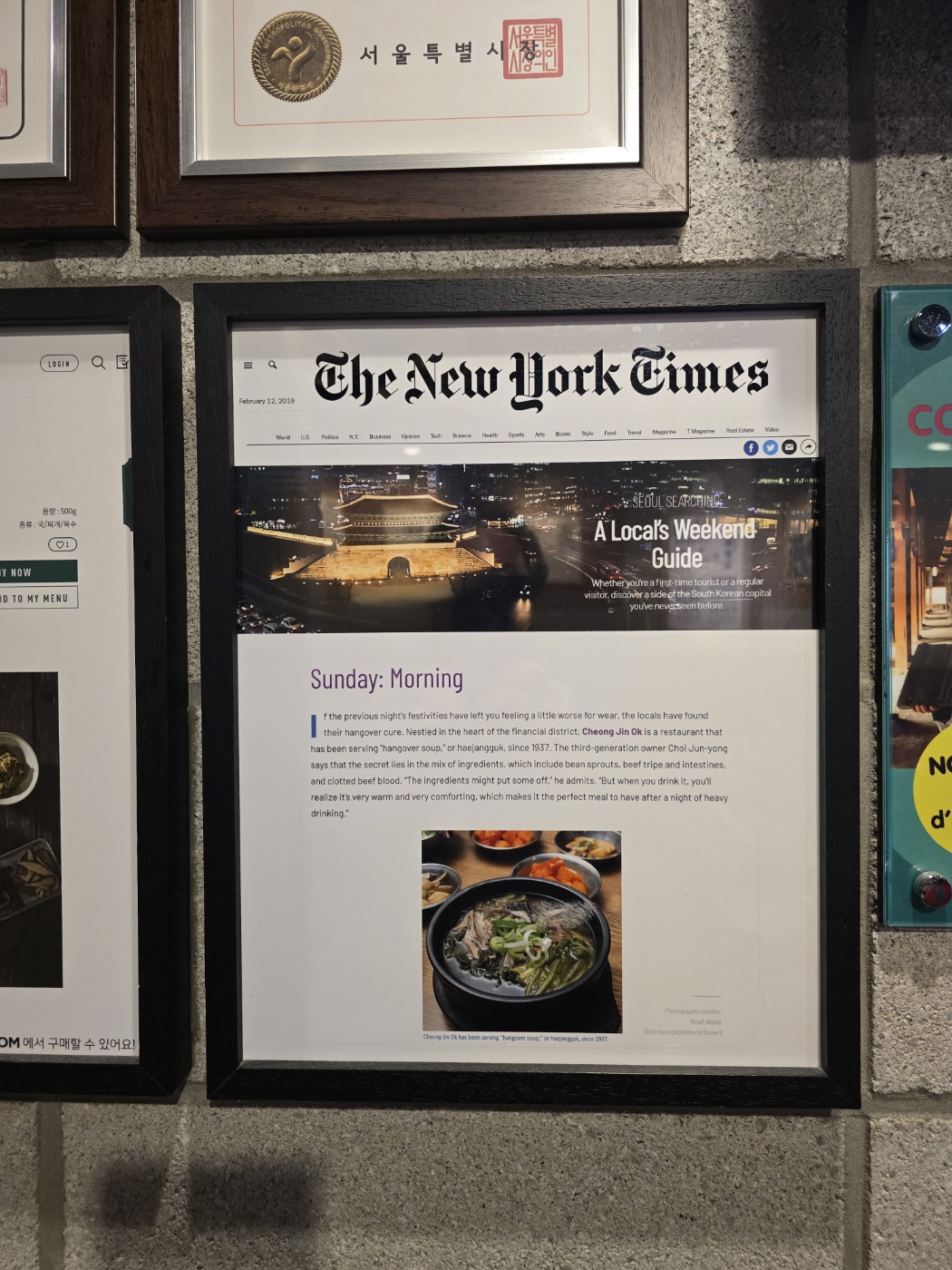

What The New York Times Discovered

When international food critics first encountered Cheongjinok, they searched for the familiar language of culinary praise: "innovative," "refined," "surprising." But those words failed. What they found instead was something rarer: authenticity without performance.

Foreign reviews often describe Cheongjinok as "authentic," but that word is insufficient. What they encounter is not staged authenticity, not curated tradition. They encounter continuity—the unbroken thread of a city feeding itself.

Nothing has been optimized for global taste. Nothing has been softened for comfort. And precisely for that reason, the experience feels sincere.

A Restaurant as Urban Memory

Cheongjinok exists in Jongno (종로), a district layered with governance, journalism, protest, and daily labor. This is not accidental. The restaurant grew alongside the city's working spine.

To eat here is to participate—briefly, humbly—in Seoul's long routine of starting over every morning. Foreign visitors often sense this intuitively. They speak of feeling like "an observer of daily life," not a customer. That distinction matters.

Cheongjinok does not sell Korean culture. It continues it.

For many visitors, this becomes their first realization that Korean food culture is not only about barbecue, fried chicken, or street snacks. It is also about endurance, recovery, and restraint. Haejangguk is a dish born from fatigue. Cheongjinok is a place that has learned how to survive fatigue.

Why the Value Endures

In an age of constant reinvention, Cheongjinok has chosen non-change. The recipe remains stable. The space remains functional. The service remains direct. This consistency creates trust across generations—and across borders.

For foreign visitors, especially those weary of globalized sameness, Cheongjinok offers something rare: a place that does not adjust itself to them. Instead, it invites them—silently—to adjust their pace.

Practical Visiting Guide

Location: Jongno-gu, central Seoul (종로구)

Nearest Stations:

- Gwanghwamun Station (광화문역, Line 5) – about 7–10 minutes on foot

- Jonggak Station (종각역, Line 1) – about 5 minutes on foot

Best Time to Visit: Morning to early afternoon (this is traditionally when haejangguk is eaten)

What to Order: Seonji Haejangguk (선지해장국)

Language Tip: English is limited; pointing and simple words are sufficient

Cultural Tip: Eat promptly. This is a working restaurant, not a café.

The Taste That Lingers

A city reveals itself not in what it shows, but in what it keeps doing. Cheongjinok keeps boiling its broth. It keeps serving the same bowl. It keeps welcoming mornings.

For a foreign visitor, this is not just a meal. It is an encounter with time—time that has not been polished or packaged. You leave without souvenirs. But you carry the taste longer than expected.

And later, when you think of Seoul, you may not remember the height of buildings or the brightness of screens. You will remember the quiet weight of a bowl that asked for nothing, and gave you a city in return.